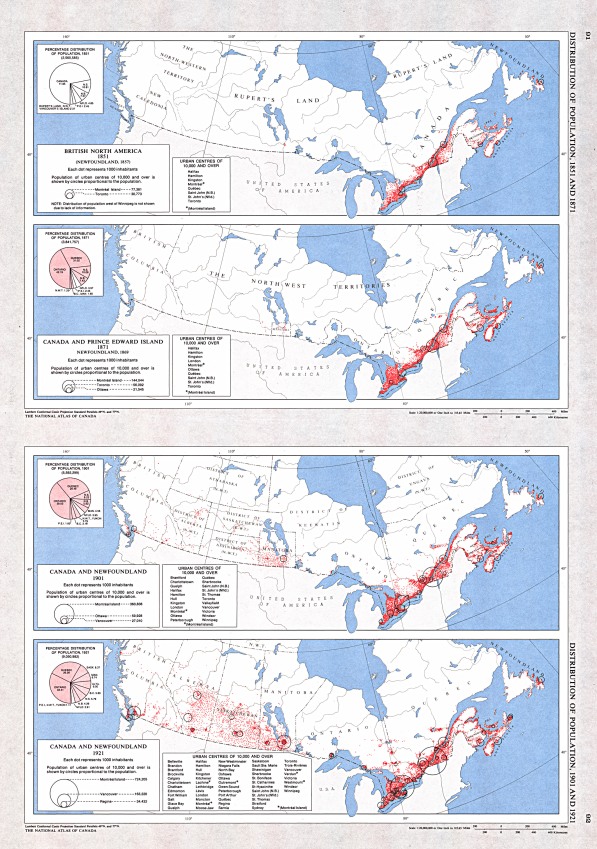

In the bottom left corner, a graph shows the 1921 population per province. Ontario’s population then accounted for 32.4% of the canandian population and Québec’s population accounted for 26% of the canadian population.

On the map, a red dot represents a thousand inhabitants. In larger settlements, red are replaced by circles whose diameter is proportionnal to population. Let’s look at the Great Lakes and St-Laurent river low lands area.

We can see that, in the Toronto aera, many circles overlap each others, more than in the Montréal area. Toronto was then, in 1921, becoming the center of a large cluster of cities and towns.

Montréal alone was then still larger than Toronto alone, but the great Toronto metropolitan area was already larger than Montréal metropolitan area. By looking at Toronto alone and Montréal alone populations, one misses the bigger picture.

So, already by 1921, Toronto metropolitan area was outgrowing Montréal.

…

Here is an interesting quote from american urbanist Jane Jacobs, The Question of Separatism : Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty :

« Montreal used to be the chief metropolis, the national economic center of all of Canada. It is and older city than Toronto, and until only a few years ago, it was larger. At the beginning of this century Toronto was only two-thirds the size of Montreal, […] »

« During the great growth surge of Montreal, from 1941 to 1971, Toronto grew at a rate that was even faster. In the first of those decades, when Montreal was growing by about 20 per cent, Toronto was growing by a rate closer to 25 percent. In the next decade, when Montreal was adding a bit over 35 percent to its population, Toronto was adding about 45 percent. And from 1961 to 1971, while Montreal was growing by less than 20 percent, Toronto was growing by 30 percent. The result was that Toronto finally overtook Montreal in the late 1970s. »

« But even these measurements do not fully suggest what was happening economically. As an economic unit or economic force, Toronto has really been larger than Montreal for many years. This is because Toronto forms the center of a collection of satellite cities and towns, in addition to its suburbs. Those satellites contain a great range of economic activities, from steel mills to art galleries. Like many of the world’s large metropolises, Toronto had been spilling out enterprises into its nearby region, causing many old and formerly small towns and little cities to grow because of the increase in jobs. In addition to that, many branch plants and other enterprises that needed a metropolitan market and a reservoir of metropolitan skills and other producers to draw upon have established themselves in Toronto’s orbit, but in places where costs are lower or space more easily available. »

« The English call a constellation of cities and towns with this kind of integration a « conurbation », a term now widely adopted. Toronto’s conurbation, curving around the western end of Lake Ontario, has been nicknamed the Golden Horseshoe. Hamilton, which is the horseshoe, is larger than Calgary, a major metropolis of western Canada. Georgetown, north of Toronto, qualifies as only a small southern Ontario town, one of many in the conurbation. In New Brunswick it would be a major economic settlement. »

« Montreal’s economic growth, on the other hand, was not enough to create a conurbation. It was contained withing the city and its suburbs. That is why it is deceptive to compare population sizes of the two cities and jump to the conclusion that not until the 1970s had they become more or less equal in economic terms. Toronto supplanted Montreal as Canada’s chief economic center considerably before that, probably before 1960. Whenever it happened, it was another of those things that most of us never realized had happened until much later. »

« Because Toronto was growing more rapidly than Montreal in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, and because so many of its institutions and enterprises now served the entire country, Toronto drew people not only from many other countries but from across Canada as well. The first two weeks I lived in Toronto back in the late 1960s, it seemed to me that almost everyone I encountered was a migrant from Winnipeg or New Brunswick. Had Montreal remained Canada’s pre-eminent metropolis and national center, many of these Canadians would have been migrating to Montreal instead. In that case, not only would Montreal be even larger than it is today, but -and this is important- it would have remained an English Canadian metropolis. Instead it had become more and more distinctively Quebecois. »

« In sum, then, these two things were occurring at once: on the one hand, Montreal was growing rapidly enough and enormously enough in the decades 1941-1971 to shake up much of rural Quebec and to transform Quebec’s culture too. On the other hand, Toronto and the Golden Horseshoe were growing even more rapidly. Montreal, in spite of its growth, was losing its character as the economic center of an English speaking Canada and was simultaneously taking on its character as a regional, French-speaking metropolis. »